Pelvic Form and Function

Anatomy

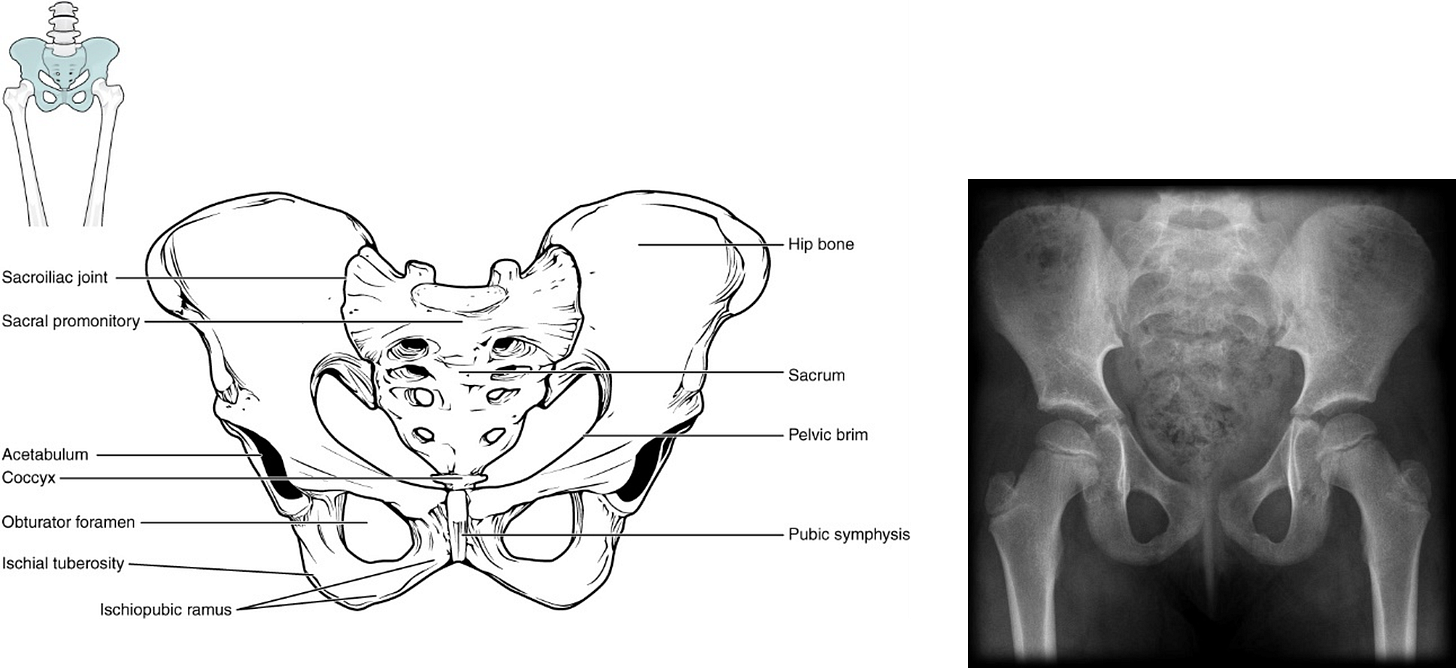

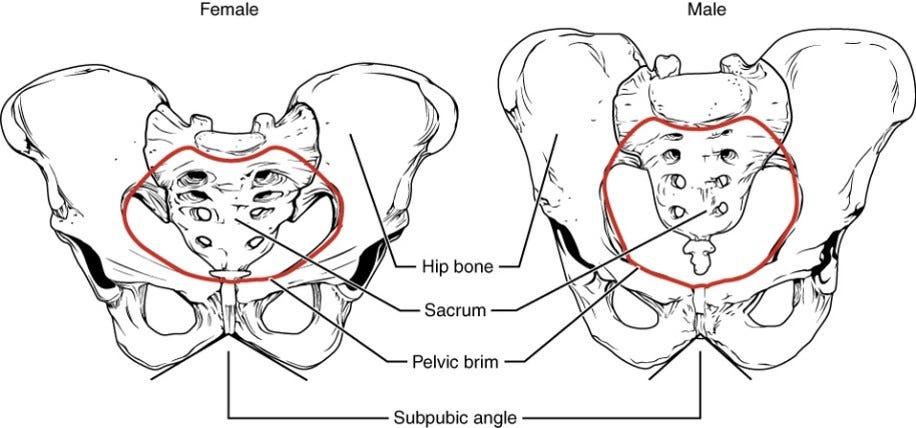

Each pelvic bone (os coxa) is actually 3 bones (ilium, ischium, and pubis) fused together. These bones usually fuse together by 7-9 years of age. In the radiograph of a child’s pelvis (click for source) on the right, you can see the bones are unfused. In the back (posteriorly), each os coxa forms a joint (sacroiliac joint) with the sacrum. In the front (anteriorly), the ossa coxae are united by a piece of fibrocartilage, forming the pubic symphysis. Anatomical features of the female pelvis (below) serve to widen the birth canal to facilitate childbirth.

Functional aspects: bipedalism

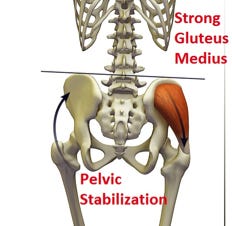

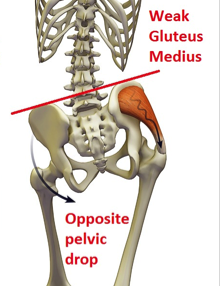

The ilium provides attachment for 2 hip muscles (gluteus medius and gluteus minimus) that attach to the greater trochanter of the proximal femur. In the image (click for source) below, you can see that these muscles travel across the side of the hip joint. Although these muscles are classified as abductors (they can pull the lower limb out to the side), their main function in humans has to do with walking. Look at the figure below: when you place your right leg to take a step (and your left leg is swinging), these muscles pull down on the pelvis (ilium) so that it doesn’t drop down. By controlling pelvic tilt, they allow for smooth bipedal locomotion (walking).

Clinical aspects

If these muscles are not functioning properly (sometimes due to nerve damage or other hip disorders), the person can’t control pelvic tilt and the pelvis will drop down (to the other side) when taking a step. The person will have to compensate which causes a characteristic gait called a Trendelenburg sign. This condition can be managed by physical therapy, exercise, and medication.

Evolutionary considerations

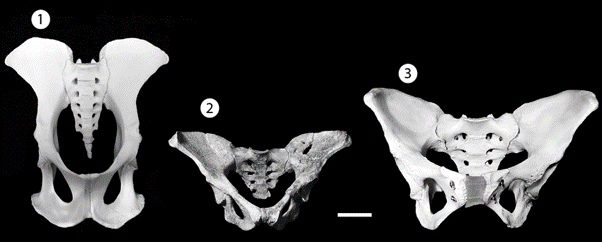

The modern human pelvic structure has been around for quite a long time, indicating that human-style bipedalism has been practiced for several million years. Below is an image (click for source) of a modern human pelvis (3) compared to the fossil skeleton (2) nicknamed “Lucy” (dated to about 3.2 million years) and that of a chimpanzee (1). Clearly, the overall shape of the fossil skeleton is much more similar to modern humans than to the ape. These comparisons suggest that the abductor mechanism for controlling pelvic tilt (and, therefore, our form of bipedalism) has been around for millions of years. A really interesting idea that has been proposed is that the shape of the modern human pelvis represents a compromise between (1) the need to give birth to large-brained infants and (2) the mechanical requirements of bipedalism.